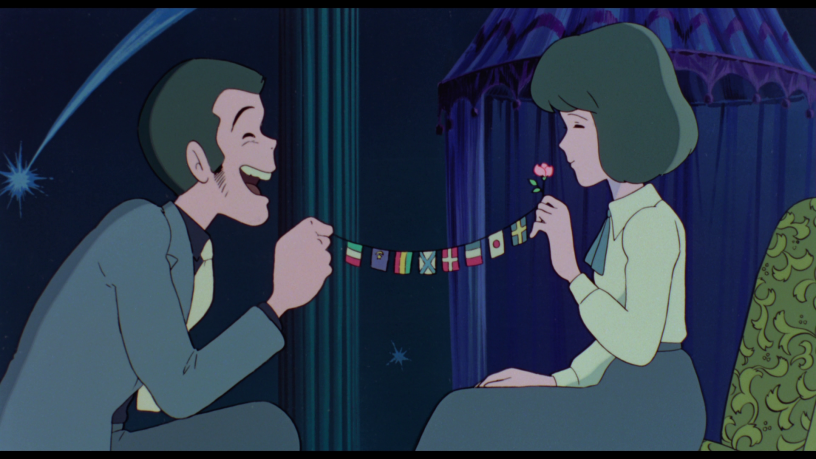

If copyright was shorter, what sort of additional creativity might be unleashed? We can’t know that for sure, but the example of the Miyazaki movie Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro offers a few possible clues.

Thirteen years ago, at the height of the fan commentary track fad inspired by a Roger Ebert column, I recorded the first version of my Lupin III: Castle of Cagliostro commentary track. It was reasonably well-received, getting mentions in a number of articles about Cagliostro, even though my audio quality was fairly terrible and it featured a number of errors I hadn’t even been aware of.

With the release of a new (amazingly well-made) Castle of Cagliostro Blu-ray, I was inspired to transcribe, revise, and rerecord the track. I finally finished the process of editing it this week, and made it available on my personal blog. Thanks to some help from Reed Nelson (whose own very excellent commentary is incorporated directly into that new Blu-ray) in catching the last few errors I had permitted to slip in, I’m confident that this is the best my track has ever been.

I had been considering posting a review of Black Coat Press’s excellent new translation of some classic Maurice Leblanc Arsène Lupin stories which helped inspire the movie, so as to have an excuse to plug it here. But as I kept researching and revising, I realized that part of the story behind the film itself was even more appropriate to talk about.

Castle of Cagliostro was based on a number of elements, many of which involved borrowing concepts from the art of others, with or without permission. Bringing to mind the expression “turtles all the way down,” Cagliostro is in some respects recursively fanfictional. But as I will explain, that’s not at all a bad thing.

Arsène Lupin and Holmsian Fanfi—ahem, Pastiche

Our story begins at the turn of the 20th century, when unsuccessful novelist Maurice LeBlanc heard from a friend of his who was starting a magazine called Je Sais Tout, or “I Know All,” in the mold of British magazine The Strand. He wanted Leblanc to write some stories that could serve as a counterpart to The Strand’s hit fiction series, which was by a fellow named Conan Doyle starring a guy named Holmes.

Perhaps it was the rivalry between the UK and France of the day that led Leblanc to want to go in the opposite direction of his British equivalent out of sheer contrariness. Whatever the reason, instead of a great detective, Maurice Leblanc invented a great thief: Arsène Lupin, Gentleman Burglar. Lupin was probably inspired in part by French anarchist Marius Jacob, whose trial at the time was a matter of much public interest. Leblanc might also have based Lupin’s name on that of Edgar Allen Poe’s detective C. Auguste Dupin (for whom Holmes expressed disdain in A Study in Scarlet).

One of the funniest things about the original Arsène Lupin was that he sometimes fought a thinly veiled Sherlock Holmes parody called variously Holmlock Shears or Herlock Sholmes. He was explicitly named Sherlock Holmes, until Conan Doyle objected—but copyright being relatively primitive back then, there wasn’t all that much Conan Doyle could do except object. (Indeed, Holmesian fanfic—called “pastiche” back then—was fairly common, as Victoriana expert Jess Nevins could tell you.) The character has been renamed back to Holmes in some of the translations made after the Holmes books started passing into the public domain.

As you might expect from a French author, English hero Shears was written pretty badly, for the sake of making Lupin look good. And Shears’s Doctor Watson counterpart, Doctor Wilson, seemed to exist solely for the slapstick purpose of collecting various amusing injuries over the course of their adventures. (Shears’ and Lupin’s rivalry would eventually inspire a similar rivalry between Holmesian and Lupine characters in Gosho Aoyama’s manga and anime Meitantei (Detective) Conan, but that’s another story.)

In making Castle of Cagliostro, not only did Miyazaki use the derived characters of the Lupin III gang (who I’ll discuss next), but he also borrowed a number of elements and characters from other stories or books in the Arsène Lupin series.

Lupin III: Fanficking the Fanficker

The character of Lupin III was effectively created as fan fiction of Maurice Leblanc’s classic thief Arsène Lupin. Translations of Leblanc’s works were popular in Japan in the 1960s, and Japan didn’t honor trade copyrights at the time so there was absolutely nothing stopping manga artist Monkey Punch from creating a derivative work of the mostly-still-in-copyright Lupin stories without so much as a by-your-leave.

It was years before the Leblanc estate ever found out about this derivative work, by which time it was too late to do much about it. They were able to require the character’s name be changed when the Lupin III anime were exported overseas, but eventually enough Arsène Lupin works were in the public domain that the name change was no longer seen as necessary. The Leblanc estate’s disgruntlement might be seen as fairly ironic, given “Holmlock Shears.”

Goemon and Zenigata: Yet More Derivation

Lupin’s companion Goemon Ishikawa XIII and his constant pursuer Inspector Kouichi Zenigata are other derivative characters.

Goemon is 13th in a line of samurai, descending from a legendary Japanese outlaw somewhat akin to Robin Hood. (The original Goemon Ishikawa was executed by being boiled alive; consequently, a Japanese style of fire-heated cast-iron cauldron-like bathtub is known as a “Goemon-bath” to this day.)

Inspector Zenigata descends from a fictional character from around the same period, Heiji Zenigata, from a series of early-to-mid-20th-century Japanese novels. So, three of the five main characters of the Lupin III franchise are actually based on earlier sources.

Castle Neuschwanstein: When Fanfiction is “Set in Stone”

Another formative influence on Castle of Cagliostro is Bavaria, Germany’s Castle Neuschwanstein, or “New Swan Stone.” This castle was built in the latter half of the 19th century by King Ludwig II of Bavaria, and was in part inspired by the works of Ludwig’s friend Richard Wagner. Who says fan art has to be limited to written fanfic?

Though architecture critics of the day scoffed at the castle as a work of garish kitsch (indeed, something else it has in common with much modern fanfic), it was hugely influential in the century that followed. Not only did it influence Castle of Cagliostro, it also inspired Disney’s Sleeping Beauty Castle, appeared in the background of the Steve McQueen movie The Great Escape, and was an exterior filming location for Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. And it inspired the animated film I’ll discuss next, which was another source of inspiration to Miyazaki.

It Makes You Wonder(bird)

But Neuschwanstein didn’t inspire The Castle of Cagliostro alone. Part of its influence was filtered through a 1952 film by French animator Paul Grimault, which was released unfinished (and without Grimault’s approval) by its producer, with a dub featuring Peter Ustinov, Claire Bloom, and Denholm Elliot. Grimault then spent the next thirty years working to get the rights back and to raise money to complete the film to his satisfaction, which he did in 1980—the year after Cagliostro.

The 1952 version is in the public domain, and can be found on Archive.org under the title The Curious Adventures of Mr. Wonderbird. The 1980 version, known as The King and the Mockingird, is available from Amazon Streaming Video. The 1980 version is the better movie overall, but the 1952 one is the one that influenced Miyazaki as a young man. It contains a remarkable number of elements that clearly inspired parts of Cagliostro—most notably an exaggeratedly high castle in the same architectural style, and a wicked king who liked dropping people down trap doors. In some cases, the borrowings are fairly blatant.

Out of these and other myriad sources came Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro—and once you’ve looked into the earlier sources, you can see the fingerprints of those previous works still present in what is also a classic of originality in its own right nonetheless.

Cagliostro Was Inspired, and Inspires In Turn

And this classic in turn went on to inspire many elements from many other creative works. Those include:

- the climactic clocktower fights from Disney’s The Great Mouse Detective and the Batman: The Animated Series episode “The Clock King”.

- the revelation of the sunken city at the end of Disney’s Atlantis: The Lost Kingdom.

- the character design of news reporter April O’Neill from the first Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles cartoon.

- Elements from Gosho Aoyama’s manga Meitantei Conan, whose anime would eventually cross over with the Lupin III franchise in a TV special and a movie (but, again, that’s another story).

Pixar’s John Lasseter, who has since met and befriended Hayao Miyazaki, has also expressed his admiration for and influence by Miyazaki (and the character of Luigi from Cars is a direct reference to Lupin III’s Fiat 500). I have little doubt many other works have also borrowed from Cagliostro here and there, more obviously or less.

Creativity Flourishes When Copyright is Pruned Back

The character of Lupin III was only possible in the first place because Japan didn’t honor trade copyrights at the time. When it did, the Leblanc estate was able to get sanctions slapped on exporting it to other parts of the world even though a number of Lupin works were already in the public domain even then. The only reason Detective Conan was able to get away with as much as it borrows from Conan Doyle and Leblanc is that more of those works had passed into the public domain by the time it was launched.

And these series, in turn, inspired me to get interested in and seek out more of the original works on which they were based.

Can there be any greater argument that the more borrowing is allowed, the more creativity can flourish? And this new creativity helps to promote the original works as well, as people seek them out to discover what was borrowed and how it was changed.

And yet we still allow corporations such as Disney to buy longer and longer extensions to copyright law that continue to make borrowing from older works harder and harder to do. (I still wonder how on earth Ernest Cline managed to borrow as much as he did for Ready Player One without getting sued.) Hopefully we’ll come to our senses sooner or later.

In any event, I hope you’ll check out my own creativity (and intensive research) on display in my Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro fan commentary track. I hope you enjoy it! You might also want to check out some of the works of Maurice Leblanc, available for download at Project Gutenberg or Google Books, including the ones I donated to Gutenberg myself.

If you found this post worth reading and want to kick in a buck or two to the author, click here.

Don’t forget that under U.S. copyright, a parody is permissible as long as you keep in mind that you must be making fun of either the story or the author not just using the plot for other purposes The assumption is that copyright shouldn’t prevent anything than a author is unlikely to do. Authors—G. K. Chesterton excepted—don’t usually make fun of their writings.

That includes story reviews, even if they reveal the plot and scholarship, even if it reveals even more of the plot. The latter is the argument I used in my dispute with the Tolkien estate’s lawyers over my day-by-day LOTR chronology, Untangling Tolkien. I critically evaluated his staging of events to see if they held together.

It must have worked because, although the case never went to trial, the estate’s lawyers bailed out just before they might have lost at summary judgment. And the judge later dismissed their lawsuit “with prejudice.” I legitimated describe and date virtually every event in the tale, all arranged in chronological order. That took months of work, since Tolkien goes out of his way to hide dates.

Actually what copyright protects is a good thing—a brilliant conceived storyline and clever characters that can be used in a series of stories or books. Nor does its end of term matter much that much. I recently started reading a book that’s one of those who takes up the Holmes tale since copyright on all but a few of the tales ended. I gave up. The author wasn’t remotely in Doyle’s league as a writer.

My hunch is that a really talented writer can create their own tales. They don’t need and typically don’t want to ride on the coattails of someone else. Nor does it hurt readers deprive them of fan fiction. They need to ‘get a life’ apart from their obsession. They need more variety in their lives.

LikeLike

I’ve always thought the idea that copyright curtails creativity is an argument with limited appeal. It has support in the fanfic community and its likes. But who else cares? Those kinds of works are not my cup of tea, so maybe my ears are just deaf.

I’m not saying it is impossible to use an other authors work as a springboard for something new. Ten or so years ago an author wrote a novel about Huckleberry Finn’s father. It was it’s own story, good enough on its own, and took only the barest morsels from Twain, but wasn’t the main focus of the book. But in most cases, it seems to me, authors who bemoan copyright limits just want to join a gravy train already on the tracks.

I remember an author who lamented he couldn’t write a superman vs the hulk story. Again, not my cup of tea to begin with, but even if he wanted to write a Gravity’s Rainbow sequel, I wouldn’t be interested because the authors I enjoy aren’t going to do that.

While I do think the current copyright last longer than need – and that Disney is corporate evil – I’m not at all worried that there is some fanfic masterpiece smothered under the law.

LikeLike