As the Christmas season rolls around again, my thoughts turn to a favorite classic movie—and what that movie has to say about customer service in the present day.

The movie is, of course, Miracle on 34th Street—the original version, starring Maureen O’Hara, Natalie Wood, and Edmund Gwenn as the man who may or may not be the real Santa Claus. Made in 1947, this classic film manages the difficult trick of being sentimental without crossing the line into maudlin sappiness, and being sweet without veering into saccharine.

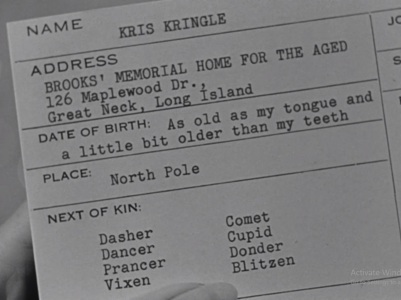

The premise of the movie is that a kindly older man by the name of Kris Kringle (Gwenn), who believes himself actually to be Santa Claus, happens to be in the right place at the right time to be hired on to “play” Santa Claus at the Macy’s department store. Along the way, he meets a Macy’s manager (O’Hara) and her precocious 8-year-old daughter (Wood), who she has been raising to eschew silly things like fantasy and imagination in favor of living in the real world. Kringle sets himself to win over the daughter, as a “test case” in whether the spirit of Christmas is a lost cause in this age of rising commercialism and cynicism—but after he locks horns with Macy’s self-important self-styled “psychologist,” Kris may be in need of a little help himself.

The movie is available inexpensively in digital form via Amazon (as well as Google, YouTube, Apple, and many other streaming video services—but Amazon’s the only one that pays me an affiliate incentive!), and I watched it with a friend the other day. As I watched, it was interesting to consider how some aspects of it still apply to the present day.

It was quaint and charming that even back then, Kris Kringle feared Christmas was getting too commercialized. (I can only wonder what he’d say about it now!) But one of the ways in which he “fights back” is to implement a policy, all on his own, of making sure that parents can get the presents their children want, even if Macy’s doesn’t stock them. When Macy’s is out of the toy a child wants for Christmas, he directs the harried mother to another store. The Macy’s manager is at first horrified—until parent after parent congratulates him on this new marketing tactic and promises they’ll be loyal Macy’s shoppers from now on.

So first Macy’s, then competitor Gimbel’s “enter into the spirit of Christmas” by directing their customers to other stores—in the interest of turning those customers into loyal customers of them. They “put the spirit of Christmas ahead of profit”—in the name of making more profit than ever.

As amusing as it was to watch these bastions of commercialism do the right thing for cynical reasons, it reminded me that one of the biggest premises of customer service as it’s understood in the modern era is to keep the customer happy. Even when it costs you something—as when, in the movie, these big department stores direct someone to another store for something they don’t have themselves—you’re likely to get that back and more just by making that person all the more likely to come to you first.

Just look at all that Amazon does. Its extremely generous return policy probably costs the company a lot more than other businesses with stingier return policies pay out—but knowing that they can send back something for whatever reason for a full refund makes people all the more likely to order from Amazon. And let’s not forget that even the idea of referrals themselves has become a keystone of Internet commerce. If you click on my Amazon link to purchase the movie, I get a cut of what you paid for the movie—and of anything else you buy from Amazon from that browser for the next 24 hours. So not only can I tell you where to go to buy something, I can get rewarded for it.

It’s also interesting to note that Miracle on 34th Street was one of the first movies to get an after-the-fact novelization (available for Kindle, too!). Indeed, the introduction to the book remarks on how odd it is that a book should be written after the movie. Like modern novelizations, it expands upon the story of the movie and fills in a few interesting details. It’s kind of ironic that a movie complaining about how commercialized Christmas has become should set an example for one of the most commercialistic trends in movies today—the writing of novelizations chiefly so that they can be faced out in bookstores to serve as miniature movie posters.

If you’re fed up with the constant bombardment of Christmas you have to put up with for 1/12 of the year, your first inclination might not be to seek out a movie about Christmas. But in this case, that would be a mistake. Miracle on 34th Street is a great antidote to the overcommercialization of Christmas. It makes its point without belaboring the point. There’s no dead horse beating here. Kris Kringle stands for what he believes Christmas should be largely by example. He might argue fervently for his point of view from time to time, but he doesn’t pontificate. He simply lives the proposition that “Christmas is a frame of mind”—and many of the people he encounters come to agree with him.

One of my favorite things about the movie is how coy it is as to whether or not Kris actually is the real Santa. There are a few places where Kris Kringle does extraordinary things, but the movie is careful to leave room for a “rational explanation” for every one of them. But that ties in with one of the main themes of the movie—that faith is believing in something when you don’t have any proof. The movie wouldn’t undercut that lesson by actually providing any.

So, if you’re looking for an entertaining movie this holiday season, check out the original Miracle on 34th Street. (Skip the remakes.) This movie remains a perennial classic—with a remarkably prescient take on what makes for good customer service.

I didn’t remember this movie, but last year’s Christmas I read a collection of Connie Willis’ Christmas stories and one of my favorites was about how much better was this movie opposite to It’s a wonderful life, I recommend it also.

LikeLike

I recommend the story, my comment wasn’t clear enough :-). I read the book in Spanish, but I think the same collection has been publish in English, looking for the author’s books should be easy to find.

LikeLike