Today I ran across the story of an established writer who was moved to write an unauthorized Narnia novel, as a labor of love. British writer Francis Spufford, author of the award-winning 2016 book Golden Hill, wrote the fanfic after his daughter asked him to write something she would want to read—and because he was also a Narnia fan himself.

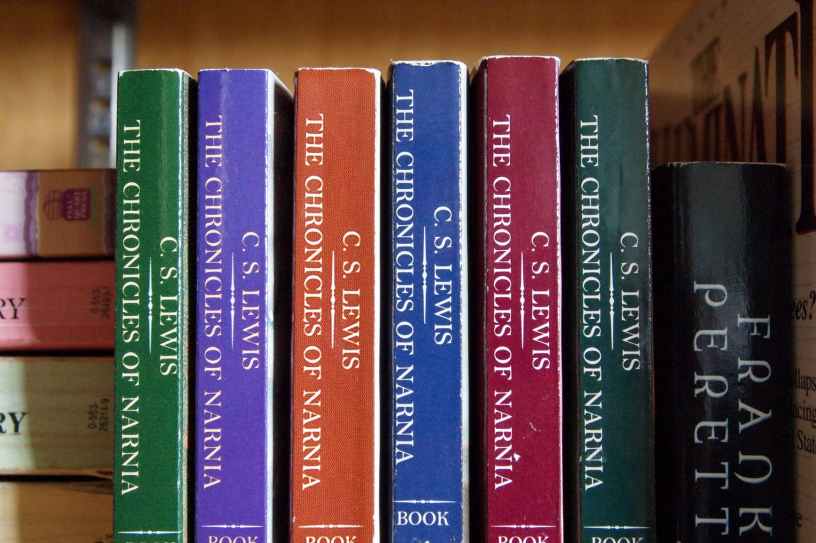

The problem is, the Narnia works are still under copyright until 2034 in Spufford’s native UK and other life+70 countries. (They entered the public domain in Canada in 2014, as Canada is a life+50 country.) The USA is a life+95 country for works published after 1978. Works published before then, assuming copyright was renewed, may be copyrighted for up to 95 years from date of publication. This means that The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, the first Narnia novel, published in 1950, will be under copyright here until 2045, and subsequent books will enter the public domain as many years later as they were originally published.

Since the Narnia books are not yet in the public domain in the UK, Spufford has approached the C.S. Lewis estate for permission to publish. He hasn’t yet seen a response. (But perhaps the extra publicity brought on by that article in the Guardian will help.)

Under the copyright laws that held sway for much of the United States’s history, those works would have entered the public domain already—but as publishers and media companies got more powerful, with more powerful lobbies, they were able to extend that period again and again. As it is now, a child could be born in the same year the first Narnia book was published, then grow old and die before the book ever entered the public domain—even in a life+70 country like the UK.

It’s a real pity, because these stories are an important part of our shared culture. It used to be that people had access to such works after a few decades, and could then freely build on them. That was the way much of culture flourished through recorded history. Mythology and folklore was built on people being able to retell and improve upon stories they had previously heard. But nowadays, people who do that run the risk of getting in trouble with the authors of those works—or with the estates or companies who otherwise own the rights.

The blog Winter Is Coming observes that Spufford hasn’t posted the book to any of the online fanfic repositories that exist—but of course he wouldn’t. Established authors don’t want to do anything to endanger their place in the establishment, and being known for flaunting copyright by broadly distributing an unauthorized work could have profound repercussions for their career. The only way such a work could be published legitimately where Narnia is still under copyright would be to have the permission of the Lewis estate.

Asking for permission sometimes works. Ryk Spoor’s excellent Grand Central Arena series prominently features characters and situations from the works of pulp SF pioneer E.E. “Doc” Smith—which Spoor was able to do because the Smith estate granted him permission. (But characters derived from other settings, such as Star Trek or Speed Racer, did have to have the serial numbers filed off.)

Otherwise, attempting to publish such works can end up in court—as with the unauthorized sequels to Gone with the Wind or Catcher in the Rye. The Margaret Mitchell estate eventually settled its lawsuit over the Gone with the Wind sequel and allowed its publication. However, a judge blocked the publication of the Catcher in the Rye sequel in the US (though it was able to be published in the UK).

If Spufford can’t get the Lewis estate’s permission, he could always publish it exclusively in Canada, and other countries where the Narnia works have already entered the public domain. But in the UK, he might just have to shelve it for 15 more years—and count himself lucky that he’ll probably still be alive by the time he is legally able to publish a book based on one of his childhood favorite series. (And also lucky that he doesn’t live in the USA, where it would be 11 more years after that for even the first Narnia book to enter the public domain—let alone all the later-published ones that would have to follow before he could safely use story elements from them.)

Canada and the UK had life+50 from 1914 – can you demonstrate the alleged cultural loss? I think you cant. The only row was about Sherlock Holmes.

LikeLike

Your response stinks of sour grapes for some reason. I think perhaps you’re playing for the other team? Of course there is cultural loss. The backbone for nearly all of Shakespeare’s plays were taken from previous sources. The ancient myths perpetuated themselves over and over again throughout history, leaving their imprint as some of the great literary works down through the ages. You can’t measure (and thus cannot demonstrate) an absence. We can’t say what isn’t there that would be if greed was not so legislated. Great writers have undoubtedly been kept from great works as a result.

LikeLike

Wow, thanks for the mention! I hadn’t seen this until now, but it’s great to be mentioned in a completely not-all-about-me context!

LikeLike

Wow, thanks for the mention! I hadn’t seen this until now, but it’s great to be mentioned in a completely not-all-about-me context!

LikeLike

Miss you, Chris! Cool article.

LikeLike